Ferdinand Ries - Piano Concerto in G Minor Op. 177 (1832)

|

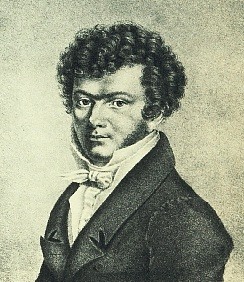

| Ferdinand Ries |

Performed by Christopher Hinterhuber. Conducted by Uwe Grodd with the New Zealan

d Symphony Orchestra.

I. Allegro Con Brio - 00:00

II. Larghetto - Con Moto - 13:13

III. Rondo - Allegretto - 20:33

Nearly eight years were to elapse before Ries composed the Concerto in G minor, Op 177, the last of his eight piano concertos. On the surface the work does not appear to represent a significant advance on the earlier concertos in its musical structures, style of pianism and expressive range. Even the choice of tonality is not especially remarkable by this time given the increased prevalence

of minor mode works and indeed it is arguably less enterprising than Ries's choice of C sharp minor in the Third Concerto composed in 1812. Nonetheless, the G minor Concerto displays a further refinement of technique in the way in which Ries organizes his large-scale musical structures and critically in his writing for orchestra.

One of the fascinating aspects of Ries's oeuvre (and Beethoven's too for that matter) is the way in which so many apparently revolutionary details in the late works had been anticipated in his earlier compositions. In the case of Op 177, for example, the opening of the movement is tonally ambiguous: it sounds for all the world as if the work is in B flat major and it is only after a few bars that one realizes that the correct key is G minor. This elliptical approach to establishing the tonic is similar to that encountered in the E flat Concerto but it is compressed in time. Similarly, the second movement, which is cast in D major, creates the illusion of a link to the Finale by suggesting that it is functioning as the dominant of the next movement, a technique he had employed in a slightly different manner in the Op 42 Concerto.

|

| Ferdinand Ries (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

been impressive from the outset of his career and his fascination with their distinctive qualities is evident in works such as the Grand Septuor, Op 25, the Piano Quintet in B minor, Op 74 and the Grand Ottetto, Op 128. His writing for horns and trumpets in his orchestral works remained by comparison somewhat limited largely on account of the physical design of the instruments. In the G minor Concerto, however, we see a new flexibility in writing for the horns, one in which the instruments play in a wide variety of keys within the same movement. Ries features the horns prominently throughout the work signalling their expanded role by assigning them important thematic material. Nonetheless, fine though the orchestration undoubtedly is, our attention is almost invariably focused on the soloist. Ries's piano writing shows no weakening of inspiration in its thematic ideas nor does it suggest that his powers as a performer were in any way diminished. The stamina required to perform the outer movements is immense and the lilting, Larghetto con moto second movement with its exquisite filigree embellishments and subtle manipulation of internal meter demands the finest of musical sensibilities to perform it as perhaps Ries himself did. It is difficult to imagine Ries's audience reacting with any less enthusiasm than they had at his numerous other premières and yet from this time on his star began to wane as younger composers and performers began to take centre stage. Within five years of its composition both he and Hummel were dead and with them the last links to the golden age of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven were severed.